by Renan Laru-an & Alfred Marasigan

I think it’s pretty violent to take away net art from where it came from, where it ended up in, or where it was neglected. These are some places that I always try to inhabit. Because when you shuttle forward always – something I also say in the book – it means you’re leaving other things behind.

Promotional image for Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan: The Taal Sea Snake Series (Vol. I) inspired by online live-selling, scientific journal designs, and 90s local TV (2020). Screenshot courtesy of the artist.

Renan Laru-an

Thank you for reconnecting, Alfred. This conversation is for Hoppla, a new platform initiated by our friends mostly based in Jakarta. They are researching net art in Indonesia and perhaps maybe around Southeast Asia.

What would be an interesting way to start a discussion of the history of net art in the Philippines is to make it more intimate and to think it through practice—through your own personal artistic history, your journey, and/or your relationship with the materials. It would be a constellation that thinks net art in the Philippines.

Thank you so much for sending the book. Let us start with the tangible printed copy of your practices, through and in Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanngan (Atemporal Sea Snake) (2020). Thinking through net art through the pages of this self-published book points us to the materiality of practices and what might be the relationship of materiality in thinking about net art, with art in virtual space, on art that emerges from the digital. Could you briefly introduce us to the project, first as a publication and then perhaps thinking about the publication (the procedure) and if you could discuss why you decided to divide it into works in documentation and production.

Alfred Marasigan

Actually, the publication for me is almost like the closing of – at least – that leg of the duhol’s journey. Because primarily the project for me is very much ephemeral. It began a “long” time ago, like 2019, and it was a project I didn’t initially imagine to be a publication. So, it was almost like a memorial of my livestreaming practice.

For its [content] division [as documentation and production], I tried to make it a little more succinct in a way but could [still] be enjoyed in a more emotional way. I don’t know, maybe because the work itself and the entire project from 2019—2021 is already sprawling as it is, and having a publication helps people somehow piece it together themselves after those two years. The book is more of catalogued storytelling of the entire project.

Book documentation via Instagram stories (2020). Images courtesy of the artist, E3 Print Hub Katipunan, Ida De Jesus, and Jord Gadingan.

Renan

The book became a temporary container that contains the sprawl, the expansion, all the things you gathered, things that you presented. Then the book also leaks into other dimensions: The book has leaks. What I also find exciting with the book is that it also presents a different kind of texture and quality and therefore I receive and “read” a different sense of information and facts of the project. I’ve watched the fragments of your documentation on your website and on Youtube, and they were also different. It seems that there are two different streams of documentation here. Why is it important for you to produce such qualities, e.g. black and white, poorly printed, cheaply printed publication? Why is it important for you to assert this kind of quality in the book?

Alfred

I made sure that, even as it parallels a lot of the project, the book is its own space or its own self. Because [I consider] every moment [of the livestream], I’m almost very adamant in not showing my livestreams again. [Rescreening] dulls the uniqueness of it being live; people have a different investment when they see it [in the moment], and the book is not a substitute [to the livestream] but a complement to that.

I worked very differently between livestreaming and publishing. It’s nice actually that you mention “the container” because I think the more that I kept working with the book design, the printing, and even its distribution, [the more the process felt] like a formalin jar. If you put something on a page, you can move it around, whereas if you are planning a live performance, you can’t really control the spontaneous things that happen – I had to learn two methods of telling the same story.

It was also important for me to create an “authentic” copy [because of these]. I wanted to really work with a local printer near me during the pandemic. I felt that the [photocopied] quality of the book anachronizes the contemporary, especially the screenshots. I just wanted people to see how easily it could be phased out, or how the “new” could be “old”. For me, it’s always a play on time, I think. After creating the book, I’ve been reading a lot about Philippine sci-fi or local horror. Sci-fi was not that much explored [for me], and mostly happens in literature. I think it fits into the same idea, like trying to reimagine, not very explicitly, that maybe the future of Philippines’ net art is that there is no future. People are only constructing every moment instead of projecting what will happen to us.

I also really like the quality of colorizing archival photographs that makes people ask “when was it actually made?” It becomes a new artifact, or a kind of remixed chronology. Whether it’s a book, or a livestream, or a performance, I wanted to play with history because it hasn’t been kind to us, and I didn’t want to obey or follow a linear stream of time.

Renan

As you underlined “the print in itself, the book in itself” as their own kinds of methodology in which you don’t want to take something out of the initial liveness of the livestream version; I imagine another discourse. It affords us to discursify a quality of our art, which could be used in talking about net art in the Philippines that could actually exist in different materials and contexts. There is recognition and refusal there to speak about it through predetermined ideas and hypotheses or in whatever normative conception of Net Art is.

Production generates a conversation, historiography, and interpretation. Historiography and interpretation should emerge with the complex accounting of production and in the complexity of producing net art, its artifact, location, distribution, etc. Within these tasks, you mentioned futurism, that this futurism that we are engaging with, might be rooted elsewhere. It has a different kind of philosophy. We’ve also experienced the “accessibility” of art across platforms today.

There is an urgency that can be articulated in production, which may be a production of the future. For example, the production of screenshots included in the book that are anachronistic as you wanted it to be. The funny thing with these screenshots as things and object themselves is that it has a “signature” and a timestamp, a mark registered when you “take a shot of it”. There is the interplay with artistic timing and how the artist wants to time these screenshots in the book. It complicates our understanding of the question, where should net art finally arrive? One can argue that the book is a net art in itself. That it is not an extension, a signature, an artifact, or documentation. It is quite enriching to consider that the configuration or formation of net art could be found in a publishing initiative. This is good because we are not just confined by one configuration of the Internet.

When something creates its own methodology, it funds other thinking of the virtual, the digital, etc. I think we have to look into other mediums as well, not just the Internet. I’d like to move into the discussion about ephemerality. I wanted to put this constellation up here: ephemerality as shown in the book with the quality of images and how it is mirroring the livestream; second, the memorial to the live quality, the aliveness; then the evidentiary position of the livestream and how the book captures the post-process. Within this constellation, what I wanted to bring in is perception. In the book, you described and highlighted the “illusive, treacherous eyes of the sea snake”. Could you speak about this new characteristic in what you just discussed as a constellation of ephemerality, aliveness, and history of futurism?

Alfred

I think it’s pretty violent to take away net art from where it came from, or where it ended up in, or where it was neglected. These are some places that I always try to inhabit. Because when you shuttle forward always – something I also say in the book – it means you’re leaving other things behind. If you just sit down and really think of what happens in a second across the universe, you would be overwhelmed to move forward. [Imagining futures] is excessive at times, but I guess it’s still productive. What was the “snake’s eyes” again? What part was that?

Renan

You said something about the snake’s eyes in the re-evaluate. I think this is the part in the introduction. Let me see.

Alfred

[My] historical amnesia of my own book (laughs).

Renan

Yeah, but you said something like the illusive creator’s eyes and you wanted to re-evaluate.. Ah, this one! You wanted to re-evaluate autonomy time, magic, and storytelling through this illusive creator’s eyes.

Alfred

Ah! Because I kind of wanted to know how it felt for the sea snake to be catalogued and to be named. So, I think that’s why I felt that the apparition of the sea snake resonated so much with me, because I think we [the snake and I] are telling each other stories that kind of fill in each other’s gaps. When the sea snake becomes the sort of avatar to looking at Philippine history, it kind of breaks away from the conventional or traditional ways that we are thinking or living through it.

I think about the shapes or the infinity symbol, too. It is very specific to us because, on a concrete level, it is literally endemic to the Taal lake, but it also transcends a lot of cultures; we [Filipinos] were not the first people who found the [sea] snake to be very fascinating. That is also what I wanted to do: to kind of complicate borders as well, to look at the back end, like, sure, people might know that the species is vulnerable from the IUCN Red List but what other stories can [the sea snake] tell?

For instance, the fishermen who catch it on their nets don’t really conserve it that much [initially] because the sea snake is all too familiar to them. When I was working with Jord Gadingan, a social worker and writer within Taal, it’s interesting to see how he managed as an animal disaster management planner recently. When Taal erupted around early 2020, people had an evacuation plan for humans, but cattle were left out of that plan, to think that these animals are always the ones plastered across images [in media]. If I remember correctly, no one died, but a lot of animals died and became the poster figures of empathy in such cataclysmic events. To me, it’s worth pursuing what animals aren’t able to tell us about themselves.

Even the taxonomical aspects [parallel the complexity] of net art: people know animals, they can google pictures of them, but then the historiography of each of them, and where they are and how scattered their holotypes are, the person who collects is different from the person who named it. All this information that says something about these animals complete and give us a fuller or more empathic – and even a more possibly magical – (not just in romanticized way but also in a scary and ambiguous sense) picture of what the climate crisis might look like, or what local or social actions look like, what collectivity looks like, or what digitization looks like [in the eyes of animals]. Jord even used the term “digital poaching” for how the sea snake can be handled and transposed like an online form or ghost. From one kind of ghost [historical] to another type of ghost [digital], it kind of meanders across all those containers that we very much need to navigate.

Renan

Maybe you could also bring us back to that journey of following the emblem, the image, the avatar or the informational artifacts or characteristics of the sea snake. The reason I wanted you to discuss it is also because of the digital fieldwork that comprises the methodology of your project. We may also put forward a reading of net art could through practices of research. Tell us more about the digital fieldwork, digital ethnography, and/or digital poaching.

Alfred

Thank you for asking that: [the answer is] there wasn’t any – that’s why I kept researching. It was such a compelling feeling or intuition, but then I think [the research process] was mostly fed by absence. Or maybe also because of distance, especially as I was doing my MA in both the Arctic and in Germany where zoological structures are also something very embedded.

Just the first encounter of “it,” not yet as a sea snake, is just me watching the Taal live or IP camera online at various intervals for hours from Berlin. The interesting thing about it is, when you look at observatories around the world like in Kilauea or in Merapi, they’re all actually “live,” so when you see their cameras, the volcanoes are moving or smoking or whatever. But for some reason, instead of a live feed, [Taal’s camera] shows a new photo every five minutes. So, it’s still live but you’re not able to recover the images from five minutes ago. Some of those that I salvaged are also in the book. It’s nice to see Taal at night with fireflies across the camera! To me those fragmented images were just fascinating to “watch”, and I felt compelled to respond somehow as an artist.

I think I was also led into this research process by opening many tabs online and ending up in a “rabbit hole.” Much of this [sporadic] method is also presented in an email art exhibition of Kiat Kiat Projects, which also came at a serendipitous time when I was itching to know what “this” [sea snake] story really is about. [Within that process, something] like finding out that my colleague Hidde [van der Wall] wrote an article about German ecologists studying Taal [was surprising to me, knowing that] he has been teaching with me for almost half a decade already.

Sometimes I’d like to believe that I am led to such confluences, ending up to that webpage in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. It’s like a logbook that details that the sea snake was collected [from Taal in 1877], but there’s no image, no jar, no dead animal. I think that gap made me feel like it’s right to create a livestream out of it as a substitute for conventional scientific research. I think that’s where art, and even net art, complements these epistemological gaps in the contemporary era.

I read the meteorological report [as a PDF] that spoke of the event, which is again, a secondhand thing, because the document is really for Taal’s 1911 eruption [by a Jesuit institution] but also retold the 1754 eruption [which is where the particular sea snake in my story resides]. When I read that and saw how five months of eruption ravaged the entire area, even rearranging the polities boundaries (city divisions where redrawn and parts like Old Taal were renamed), it felt so scientific (?) and then I started fully crying, at parts of it that also weirdly put me in the position of the [Spanish] priest [in the report]. It put me in the position of the “discoverers,” [which then becomes] a complex exorcising of postcolonial affect that happened in a single moment. I wanted to read it in front of the Global Northern audience just so they would know how the body feels confronting a story that even I – who is supposed to identify most with it – am estranged from.

The entire journey of curiosity – the need to know, understand, or feel, constitutes the entire research process that I feel people are sometimes burdened by [in art?] because they would need to read a lot. But then if you research by curiosity, it’s very much like journalism. But then journalism [combined with] detective work, archaeology, but then of things that might not have happened, allows for artmaking and speculation to play a crucial role. Add to that being a bit of a hacker (?), and a bit of being a bureaucrat, between asking for permission to view archives and stealing PDFs from Sci-Hub. All these permutations of acquiring different types of information have the underlying desire of wanting to understand not only what the sea snake felt, but what scientists felt, what people in power felt when they were naming the world. Were they just doing it as a job? I mean in expeditions, we don’t really know if they actually [or emotionally] really wanted to discover these for themselves. Such affective elements are interesting to me because I don’t get that perspective much in “objective” literature. That’s what I think my research process and artmaking attempts to address in Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan.

Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan ritual and livestream with artist (left) and collaborator Maarten Keus (right) invoking the duhol matapang / Taal Sea Snake / Hydrophis semperi in front of the Cathedral of Our Lady / Vår Frue domkirke in Tromsø, Norway (2020). Image from book courtesy of the artist and Mihály Stefanovicz.

Renan

The term “postcolonial affect” that you mentioned is a vector that is important to highlight. It helps us unpack practices and subjectivities that relate to what could be the historiography of net art in the Philippines, what makes up a net artist in the Philippines, and how it can actually inflect the formation of a very young discipline? When you invoked postcolonial affect, and then later you returned to it asking yourself what the snake felt and you were interested to know what the priest felt and all the other actors in a colonial milieu, a technology reveals itself and it is being brought into the landscape, the network, the world in itself of net art; whatever that world is, the world of algorithms that we know and we don’t fully know that we all have access to and we kind of cultivate as we use Zoom and all these materials right now, but we also don’t fully know what it looks like. It is the same with your snake. It is fed by the absence or not knowing what the form is. It is paradoxical to historicize net art for example, which is of course a daunting task, but it is almost like a self-defeating task because I think you can only do it by learning other histories within the practices of art-making.

You also noted that in doing this project you were a hacker and a bureaucrat. I remember what Farabi speculated in the lecture that you also attended about a managerialism of jihad, for example, in terrorism. […] I am also imagining net art, how it is produced by specific geopoetics on one hand and by geopolitics on another. It is really becoming ecological, meaning you can’t extricate one thing from another, say in talking about materiality on the Internet and in painting for instance. It reminds me of your early painting practices.

The sea snake is endemic, which is a “critical” species that could also mean it is producing endemic qualities. The duhol matapang then can almost be imagined to be endemic in other places or in other production of a volcano. That one can actually multiply the endemicity and I think this could be a characteristic of net art, where it is not reduced to conceptualism and instead it becomes a study of materials, tools, positions, etc that can be produced actually. A kind of very flimsy attachment to things, quite deceitful in a way—these relationships and I get that sense from the sea snake.

Alfred

I also like what you said about the endemicity of the duhol because I think when we speak of net art, I think we have to be very specific all the time. Talking about net art that way breaks down compartmentalization and encourages looking at the nodal history of ideas instead of following the same line, heritage, or genealogy. One is just looking at one “branch” [or “vein”] of it. Probably tangential, but it’s also strange to me that I was led to the snake because it’s unusual (being a sea snake in a volcano). Maybe it reinforces the uncanny quality of net art. It’s really hard to “place” sometimes, but you know “where” it is: it’s in Harvard! But is that it? When one, then, expands this spectral story, you really have to rely on that flimsiness. Similarly, in paranormal terms, an ectoplasmic approach is inevitable because you need to hold some sort of belief hoping it will lead you somewhere. Anything can be true or false everywhere if you look at net art. There is this “raft of reliability” of what is objective: what is proved can be broken down because of voices that emerge from this same type of process.

Renan

That’s what I wanted to surface here maybe for Hoppla or for friends in Jakarta to highlight or to take note of: the emotionality that is not versus algorithm, not versus internet, not versus anything. There is also an emergence of artists, usually coming from postcolonial and decolonial lived experiences, who without overperforming these identities, are not so much invested in the versus or the contra all the time. It means that how you position emotionality is not a solution. It is another reliance. I like the term that you used “the rough reliability”. I think we can commit ourselves to a certain belief system, say “rough reliability” which is an honesty that could be mobilized in historicizing net art or any kind of artistic practices. Knowing emotionality and how this emotionality is material in itself and also this roughness of reliability, meaning it is a technology, it is a tool.

Let us discuss two terms that you used to describe the project: “collaborative” and “occurrence”. It has helped you define the performance as a “collaborative occurrence”, which might be a little bit different from synchronicity. It is also different from collectivity. Maybe you can speak about collaborative occurrences and then perhaps you can bring that in relation to the series or the surreality, which goes to the discussion of language, referring to how you give the title to the project in its English translation is The Atemporal Sea Snake: the snake, the infinity and the surreality of this infinity. Could you share more of your thoughts on collaborative occurrences as you use it in relation to surreality?

Alfred

I think for “collaborative occurrences,” I did commit to using that from some cursory Wikipedia search about ‘happenings’ or ‘events.’ To me, ‘occurrence’ specifies something but doesn’t make it special. It happens, the art is in there, but it’s not exclusive. It’s once in a lifetime, but it’s not a milestone. I still wanted to draw attention to the borders of such space and time, so that’s why I chose that term [to describe my medium]. “Collaborative” also acknowledges everything, everyone, or every other force that contributes to it, like in a storm or a wedding.

I use the term because I didn’t want to commit the same mistakes of excluding even if I was collecting. I am also probably trying to hold onto the moment but making sure I wasn’t very scared to let it go as well. For an entire year talking about archives with Het Nieuwe Instituut’s Collecting Otherwise initiative, I consistently brought up temporality – sharing the power of archiving also means letting go of it. Losing then [instead of acquiring] becomes important, and we fight for it and create new conditions if and even as we so desire to bring it back.

With net art, most of the things I have seen that really resonated with me a lot are those that have soul. That’s hard to harness, and that’s why I guess [art] is always a continuous process. What was the last one?

Screenshot of Taal at dusk from its PHIVOLCS’ Observatory in late 2018 before it erupted in 2020. Image from book courtesy of the artist.

Renan

Occurrence and then.. I think I also get into the practice and form of reading. In Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan, you read the entire text that you found online. One of the sites of interpretation and problematization in all art that emerges, including net art, is the artist reading himself. I think the rereading and the revocalization are not quite special nor excessive. Maybe you could speak about the practice of reading, what reading is for you right now especially seemingly there’s also paranoia that reading has changed because everyone is on the internet which of course it could be another conversation.

Reading is just really beautiful. And of course, no one wants to use the word ‘beauty’ sometimes in net art. I don’t know but there is also something about digital art and also the kind of hacking culture, there’s also a kind of antagonism to the beautiful and of course maybe it is a different relationship to beauty, but for me, I found it truly beautiful just the act of reading. Maybe you can speak about that in relation to the conditions of change, meaning it was livestream. So reading, live streaming.

Alfred

Reading the 1754 text in the livestream was important as a project of reconnection. That orality also reflects chanters reciting epics or tagulaylay from memory, and I feel it reverberates across cultures. The voice also attempts to infiltrate most of the project’s source texts written in German, Spanish or English, none of which are in our native language/s. In another sense, having it read again as a book, as a process, as research, I think was also vital because Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan and the entire Taal Sea Snake Series is another mode of stalling time, like just lying down and reading a [physical] book. It’s something I owe a lot to my conversations with Czar [Kristoff] as well and his publishing practice.

At first, I had apprehensions in “closing off” the project as a book. It felt like reverting to the colonial and published format of research and monographs that I worked so hard to exhume and liberate the sea snake away from. But then I remembered one advice from my MA mentors that there is still merit in repetition because it’s not always the same agency when a different person does it. I think I became more empowered in feeling that I was the one who is writing it down this time. I feel like it’s in the same spirit of sharing it, but not in the way that it takes more than it gives.

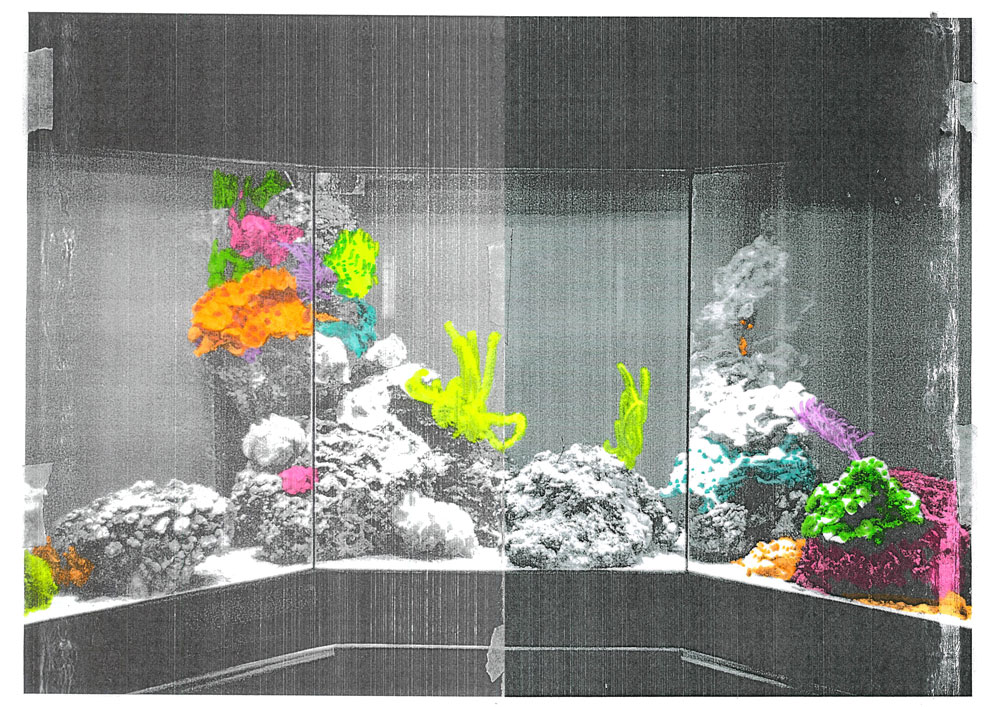

A fish tank from Aquarium Berlin’s Zoological Complex built in 1913 (2020). Image from book courtesy of the artist.

A lot of what inspired me also is from magic realist texts like Marquez, Borges, Samar, a lot of them are written, even a Magic Realist Bot on Twitter. I was challenged to replicate how it translates to visual art, specifically because magic realism allows the imagination to play with the language in a more open-ended sense. So I feel now that while I am at peace with its published format, I still insist on Ang Duhol ng Walang Hanggan as “ongoing” as a homage to its live quality and its readers’ prospective agencies.

Renan

I think these are generative nodes to temporary close the discussion. We are not into concluding, accomplishing, and completing. I think what was interesting really with what you said is about analogy and I think again I always said this, and hopefully, I am not becoming a preacher of the anti-content regime, but it’s just an acknowledgement of how difficult things are because there’s too much content. And I feel like there’s a crisis and it is recognizing that we’re also having problems finding new analogies or electing analogies to what we can do. Perhaps that’s where exhaustion, frustration, and disappointment are placed in terms of aesthetic production, conditions of production. But I think it is very interesting for you to mention the promise of analogy and how we can actually coalesce text. It also has to do with what kind of traditions of where we can actually appoint the tradition of net art if we were to appoint a tradition. I think this is been a very interesting discussion, Alfred. I have a lot of things to unpack. I’ll stop the recording now.

The Authors

Renan Laru-an

Renan Laru-an is a researcher based in Sultan Kudarat, the Philippines. He creates exhibitionary, public and research programmes that study ‘insufficient’ and ‘subtracted’ images or subjects at the juncture of development and integration projects. Current ongoing projects include But Ears Have No Lids (2021) and Promising Arrivals, Violent Departures (2018).

Since 2017 the Public Engagement and Artistic Formation Coordinator of the Philippine Contemporary Art Network, Renan Laru-an is a curator of the 2nd Biennale Matter of Art 2022, Prague and has co-curated the 6th Singapore Biennale (2019), the 8th OK.Video – Indonesia Media Arts Festival (2017), and the 1st Lucban Assembly (2015). He is Curatorial Advisor to the 58th Carnegie International 2022, Pittsburgh.

He edited Writing Presently (2019), an anthology of art writing on the Philippines today.

Alfred Marasigan

Alfred Marasigan (b. 1990) is an artist and educator who conducts serendipitous research and transmedial practices primarily through livestreaming, heavily inspired by emotional geography, Norwegian slow TV, and magic realism. Such format, often via social media, anchors his current explorations on simultaneity, sustainability, solidarity, and sexuality. Marasigan graduated in 2019 with an MA in Contemporary Art from UiT Arctic University of Norway’s Kunstakademiet i Tromsø and is a Norwegian Council of the Arts Grantee for Newly Graduated Artists. His work has been exhibited, screened, and published by Asia Art Activism (WWW/UK/PH), Tromsø Kunstforening (NO/PH), Goldsmiths’ EnclaveLab (UK/PH), Further Reading (ID), Meinblau Projektraum (DE/PH), M:ST Performative Art (WWW/CA/PH), C3 Contemporary Art Space (AU) and the Cultural Center of the Philippines (PH). Currently based in Manila, he is a faculty member of Ateneo de Manila University’s Department of Fine Arts since 2013.

Alfred Marasigan biography photo © by Lisa Robert.

Leave a Reply